Doha is a boom city on the Arabian littoral and the singular pre-eminent urban agglomeration on the low Qatari peninsula. Like many other cities on the coast of the Arabian Peninsula, the city has long been entwined in the maritime trade routes of the Indian Ocean world. The city grew around the native pearling industry while simultaneously adjusting to a variety of imperial, colonial, and tribal engagements. Hydrocarbons were discovered in 1939, but their exploitation and a sequence of further discoveries would escalate only in the waning decades of the twentieth century. The wealth generated by those resources was substantial, and much of it has been expended on the urban development of Doha. Considering the longue durée of Doha’s history, this wealth and the city that has resulted can be seen as relatively recent developments.

[Abandoned Spaceship (2008). Image by Kristin Giordano. This abandoned project was later razed.]

The periodization of this city’s history is the subject of a scholarly conversation, but against this backdrop of events the city has grown from a port of less than thirty thousand inhabitants in the mid-twentieth century to today’s cosmopolitan extravaganza of well over a million people.[1] Indeed, that number is predicted to soon double. The city’s astonishing growth has emerged as the keynote of Qatar’s global engagement. In its contemporary manifestation, Doha is characterized by the striking modernity of the urban built space, and perhaps also the pace of social change for the inhabitants therein. Those inhabitants include Qataris, who number less than three hundred thousand, but also more than a million other people who come and go as guests of a sort, mostly to work. While Qataris and the city itself are most certainly on a global stage, the proportions of this demographic concoction are fairly unique to the Gulf, as are the petro-dollars that fuel it.

While Doha and the other emergent Gulf boom cities have increasingly been the focus of scholarly attention, this short essay suggests these preexisting analyses elide a notable spatial discourse that undergirds urban development in Doha. Among other attributes, this spatial discourse is an essential feature of how Qatar and Qataris regulate, govern, and conceptualize the (perhaps unrivaled) flow of foreign matter to the small, wealthy peninsula. Two concepts here merit further explanation. By spatial discourse, I mean a fundamental pattern that shapes urban development and urban planning in the city. By foreign matter, I borrow (and perhaps misinterpret) Paul Dresch’s description of the impactive role that the region’s long interactions with regional and global foreigners have played in shaping these societies’ cultures. To quickly deploy those two concepts: the architectural creativity witnessed in the city and the agency of the urban planner are facets of a more comprehensive and historical field of arrangements.

Qualities of this spatial discourse describe it, and while this spatial discourse has some bearing on what is being built in the city, it is most visible in the arrangement and organization of what is built. One notable quality of this spatial discourse is the expanding scale of development planning. In Doha’s recent history, increasingly large geographical portions of the urban landscape are encompassed in singular planned ventures. Zones, partitions, walls, enclaves, and compounds are familiar aspects of everyday life in Doha, and are instantiations of this spatial discourse. These are the “zoning technologies” that demarcate the increasingly large units of urban planned space in Doha.

[Giant Wall (2010). Image by Kristin Giordano. Walls are the most obvious manifestations of what Aihwa Ong calls “zoning technologies.”]

Numerous illustrative examples are at hand. Constructed on a “reclaimed” island, The Pearl-Qatar is a vast urban development consisting of fifteen thousand upscale dwellings and an abundance of public commercial space. It is notable for being the first land in Qatar that foreigners could purchase. Education City, elsewhere in Doha, is a conglomeration of Euro-American universities and other important institutions, most of which are devoted to higher education. The Aspire Zone, sometimes called Doha Sports City, is a large area of the urban landscape devoted to stadia and other athletic facilities. It played an instrumental role in Qatar’s success in attracting a variety of international athletic events. And Msheireb Properties’ self-titled urban project, Msheireb Downtown Doha (originally called “Dohaland”), consists of more than a hundred buildings. Those buildings and the thirty-one hectares they occupy are arising in the dense historic remainder of the city. These are only four examples from a field of many. One characteristic they share is their expansiveness in the urban geography of Doha. The expansive scope of development planning in Doha is a key feature of this urban spatial discourse.

In addition to these four impressive developments, however, there are other sorts of examples that also illustrate this urban spatial discourse. The city’s urban landscape contains the “Industrial Area”–an urban zone on the current periphery of Doha where tens of thousands of transnational laborers dwell in dormitory camps amidst a checkerboard of light and heavier industry. Foreigners of the professional class are typically placed elsewhere–in compounds of apartments and villas. These compounds congregate in other districts of the urban landscape. Other portions of the city consist of “Qatari neighborhoods”–substantial tracts in the urban landscape where Qataris build private homes.

In his essay Foreign Matter: The Place of Strangers in Gulf Society, Paul Dresch identified the accommodation of “foreign matter” as an integral feature of contemporary Gulf societies. My interpretation of Dresch’s concept illuminates Doha’s urban spatial discourse. In some of the examples already discussed, “foreign matter” is embodied. Humans of various ethnicities, nationalities, genders, and classes are spatially sorted, segregated and placed by this spatial discourse. Unskilled Nepali migrants end up in the Industrial Area. Foreign professionals (people like me) end up in compounds. Qataris find houses and reside in “Qatari neighborhoods.” This segregation of people, as foreign matter, is the most visible purpose to which this spatial discourse is harnessed.

Yet this same urban spatial discourse also seemingly segregates other sorts of matter. Consider the examples already mentioned. The Pearl-Qatar is an exceptional space, noteworthy for being the first location in Qatar where foreigners could own property. Education City, a socially exceptional space, provided one of Qatar’s first gender-mixed educational spaces. Add to this short list the fact that the purchase and public consumption of alcohol is allowed only in designated spaces in the city, or that certain areas of the city populated primarily by European and American professionals have uncensored access to the Internet. The consignment of these various activities and relations to designated, exceptional spaces is another facet of the foreign matter being compartmentalized by this urban spatial discourse.

[Monolith (2008). Image by Kristin Giordano. A structure on the campus of Education City.]

This urban spatial discourse, and the spatialization and enclaving of foreign matter that results, can be understood as a strategic engagement with global and neoliberal flows. This is the crux of Aiwha Ong’s ideas about neoliberalism and sovereignty in the contemporary era. In her analysis, Ong was primarily concerned with issues of political economic sovereignty. In that prism, the proliferation of “free trade zones” punctuating the space of the contemporary nation state was not a happenstance development. Instead, states were developing these exceptional spaces to attract investment from global flows of capital. Spatialized exceptions to national sovereignty, Ong contends, allow the preservation of the state’s sovereignty amidst this competitive environment. In the contemporary era, the state’s sovereignty is graduated rather than uniform in space.

In Doha, I observe the same spatial mechanics at work. But in the final accounting, the impetus for this spatialization in Doha seems to be less about a political or even economic sovereignty, and more about establishing a broader sense of cultural sovereignty. Enmeshed in decades of unrivalled flows of “foreign matter” to their state and to their city, in Doha this urban spatial discourse compartmentalizes that foreign matter into an array of exceptional spaces and zones. Mixed gender campuses are a sociocultural exception allowed in particular spaces of the urban geography; alcohol consumption, a culturally moored practice in many other parts of the world, is allowed in a constellation of other exceptional spaces in the city; sustainability, as a practice tethered to a global index of modernity, is to be implemented and practiced in another designated zone (“Energy City”). In this transnational, cosmopolitan, and neoliberal environment, the compartmentalization of foreign matter –people, practices, and ideas– is fundamentally an assertion of cultural sovereignty over the domain punctuated by these exceptional spaces. Put another way, this urban spatial discourse is an assertion of Qatari cultural sovereignty over the cosmopolitan and transnational heterogeneity so essential to the developmental goals of state and citizenry. This urban spatial discourse reflects the relationship between a people and the foreign matter they both host and depend upon. This relationship is woven into the shape of the city.

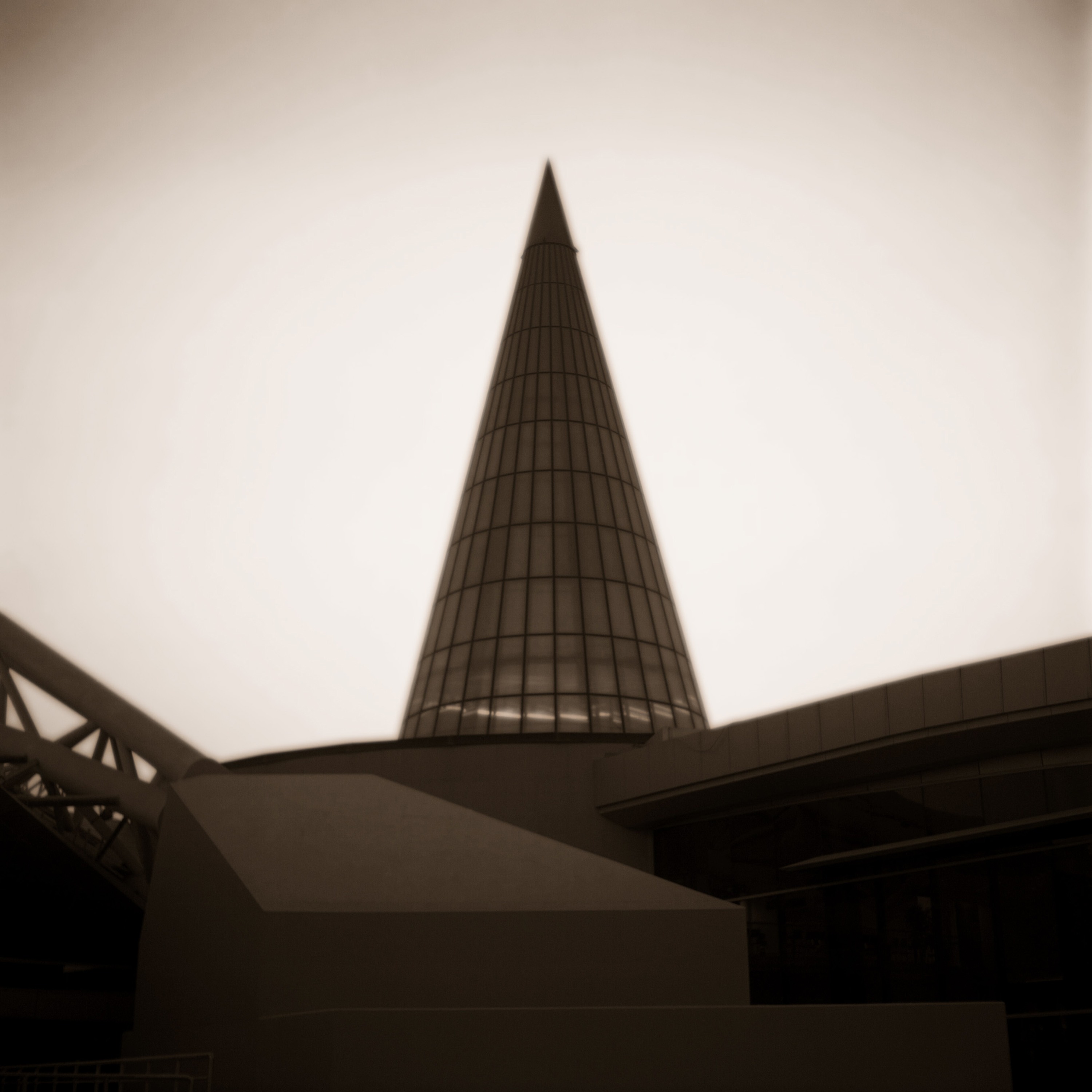

[Spire (2010). Image by Kristin Giordano. The striking modernity of Doha’s

contemporary urban development is characteristic of the city.]

Landscape and Transformation: Photographs of Doha, Qatar is the title of a new exhibit of photography currently showing at the Kittredge Gallery at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington. Photographer Kristin Giordano lived in Doha between 2008 and 2010. As a collection, these photographs explore and document the built space of the city and, in a more oblique fashion, the lived experience of dwelling in a city amidst such continual transformation. Kristin is also my wife, and during our two years in Doha, we had an ongoing conversation about how to unpack the urbanism all around us. While the photographs in this exhibit are most definitely hers, they reflect multiple aspects of the reading of the city I have just elucidated.

Giant Wall (2010), for example, is a material manifestation of Ong’s “zoning technologies” -- the mechanisms by which space is delineated in the urban spatial discourse of Doha. Walls are an integral and commonplace feature of Doha’s historic built form, and they are an essential feature of the modern built form as well. Yet while some of these images illustrate technologies for the compartmentalization of foreign matter, many other images move inside those walls, zones, and partitions to explore the content of these exceptional spaces. In Monolith (2008) and Georgetown (2008), for example, we see the monumental architecture of Education City. In Spire (2008), we see the Aspire Zone as a spatial subject. By engaging the architectural (post)modernity of the urban form, the exhibit suggests the urban spatial discourse of Doha is syncopated with the extrapolations of modernity in both architecture and urban planning.

[Venice in Qatar (2010). Image by Kristin Giordano.]

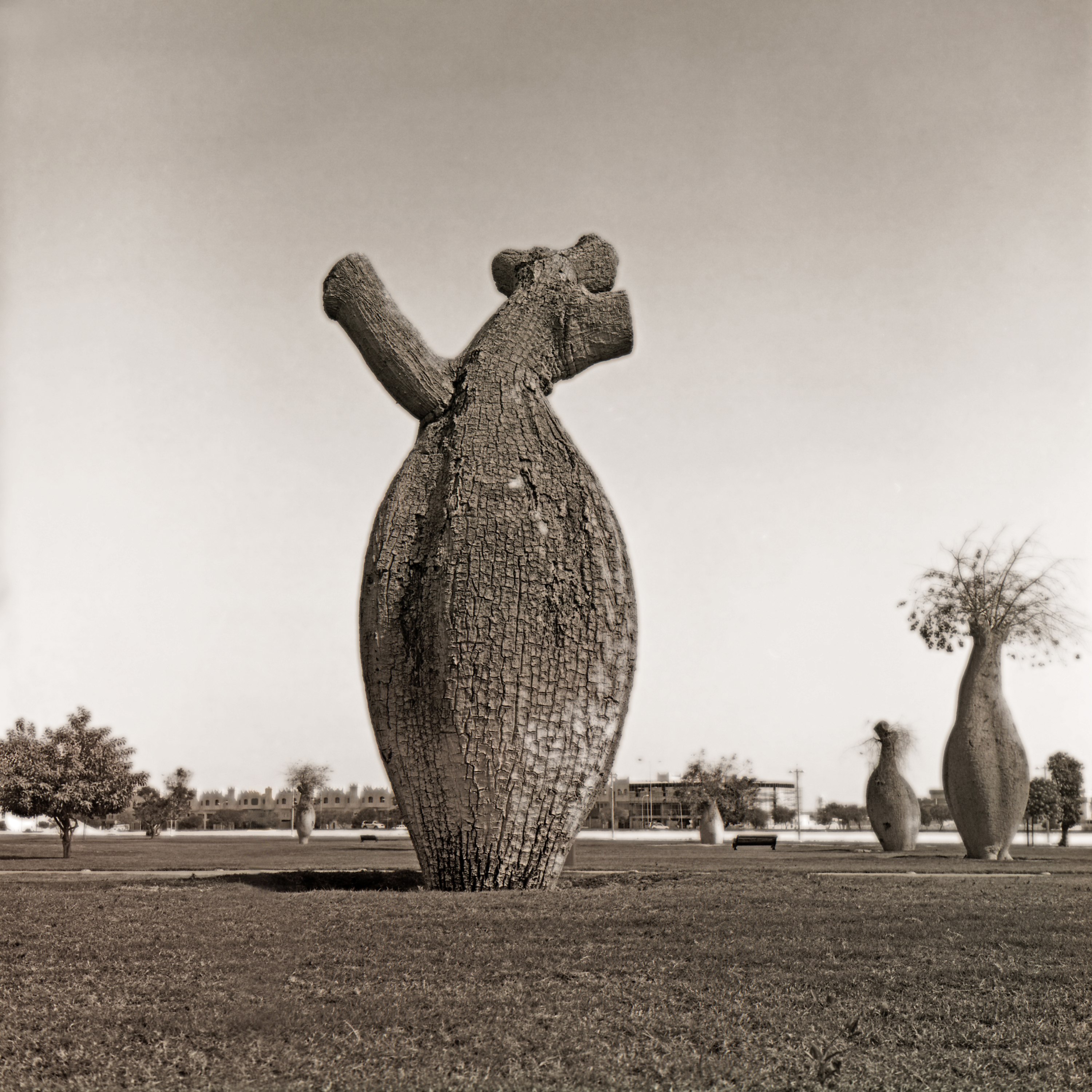

One is also struck by the open urban spaces in these photographs. The open spaces we see are punctuated by trophy architecture (Abandoned Spaceship (2008), by the machinery and detritus of infrastructural development (Two Reels (2008)), by billboards that portray a future that will soon arrive (Magic Carpets (2008) and Venice In Qatar (2010)), and by odd specimen/trophy trees that have survived a long journey to Qatar by ship (Transplanted Tree #1 (2009) and Transplanted Tree #2 (2009)). These structures and objects are interesting in their own right. But around them, open space is everywhere. This open space, or what I have elsewhere referred to as interstitial space, is the by-product of this urban spatial discourse. The energy, capacity, and focus of urban planning is delimited to the very zones and spaces it produces, the units of urban development. Unkempt, unplanned, open, and empty spaces comprise the interstices of these units of planned space.

In terms of the lived experience of dwelling in such a city, the portrayal in the exhibit is much more oblique. In the photographs, we see images of the future, the spaces of a future that has already arrived, and the structures that have already been built. Other than representations on billboards, however, there are no humans to be seen. Perhaps this absence speaks to the lived experience of this city, of an urban encounter with a city of trophies. In Doha, impressive monuments and architectural structures engage the inhabitant the same as the photographer – as objects. They engage denizens and visitors as totems of a contemporary (post)modernity, as cosmopolitan feats of design, as architectural spectacle. In that sense, these images use the relationship between photographer and subject to convey the lived experience of dwelling in contemporary Doha.

[Transplanted Tree #2 (2009). Image by Kristin Giordano.]

________________________________

[1] See Agatino Rizzo’s article Metro Doha, in Cities, for a discussion of this periodization of Doha’s urban history.

[The author would like to thank Claire Beaugrand, Sharon Nagy, and the many others who commented on various manifestations of this essay. Versions of this paper were presented at the American Anthropological Association’s Annual Meeting in 2009, at NYUAD in 2012, and at the American University of Kuwait, at QFIS in Qatar, and at Sciences-Po in Paris in 2013. The images that appear in this essay, from Kristin Giordano’s exhibit "Landscape and Transformation," were used with the permission of the photographer.]